Authenticity and Discomfort

On the Quixotic Search for an "Authentic" Educational Experience Abroad

This will be the first in a vaguely planned series of posts on the concept of authenticity (and its discontents).

In a former life that seems as distant to me now as the one in which I engaged in activist cosplay, I wanted to work in the American study abroad industry, or “international education.”1 But at its core, international education in the United States is, like anything else in that country and most other countries, a capitalist enterprise, for undergraduate study abroad is about more than “broadening horizons” and “gaining invaluable international experience,” or any other canned cliche the industry uses to market itself to students, parents and universities alike. At its core, international education is the provision of a service (facilitation of a semester/year abroad) to a target demographic (American undergraduates).

As someone who spent a year in Chile while in college, and then lived for three more years in Argentina after college (where I focused the studies I coupled with said activist cosplay on the topic of “student culture at the Argentine public university,” broadly speaking)—you can read more about that here, I was an ideal candidate for a job in international education. With my extensive knowledge of the ways in which the American undergraduate and the undergraduate systems of these popular South American destinations differ,2 I was ready to help any and all bright-eyed undergraduates preparing to embark on a semester of year abroad south of the border.

But this isn’t about the study abroad industry and why I ended up not pursuing that path, or capitalism (neoliberalism) and international education. What I want to focus on here is instead the concept of “authenticity” and the role it plays in the imagination of a certain type of American undergraduate student that is drawn to the Southern Cone. A certain type that I know well, because I was once one of them.

Many, if not most, American study abroad programs in Chile and Argentina—and I’m limiting myself to these two places, as they are the ones I feel the most qualified to discuss—send their students to local private universities, as these tend to be better organized, have nicer looking facilities and campuses, provide more extracurricular opportunities for students, and in general, are just more used to receiving international students (private universities have a much longer history of internationalization than state ones). Private universities often also provide special classes on local history and culture tailor-made for foreign students, given either in English or in Spanish by professors who are conscious that they are teaching to non-native speakers. But the issue for some American students with private universities isn’t necessarily tied to the actual quality of the education3 but with what they perceive as a sterile, often ghettoized, “inauthentic” educational environment no different from the one back home. Familiarity, in this case, breeds contempt.

Enter the public university.

A few American study abroad companies and programs facilitate enrollment in the local public university, usually in the humanities and social sciences faculties. This experience is billed for “adventurous” and “daring” students who “aren’t afraid” to “tackle the challenge” of navigating a “completely foreign” academic system and environment. In the case of Buenos Aires, this means enrollment in la UBA, or the University of Buenos Aires/Universidad de Buenos Aires, and in the case of Chile, this tends to be enrollment in la Chile (Santiago’s University of Chile/Universidad de Chile).4 This section from an online handbook for the Middlebury College program in Argentina and Uruguay provides a handy and informative overview of the differences, broadly speaking, between local public and private universities, as well as between local higher education and US higher education.

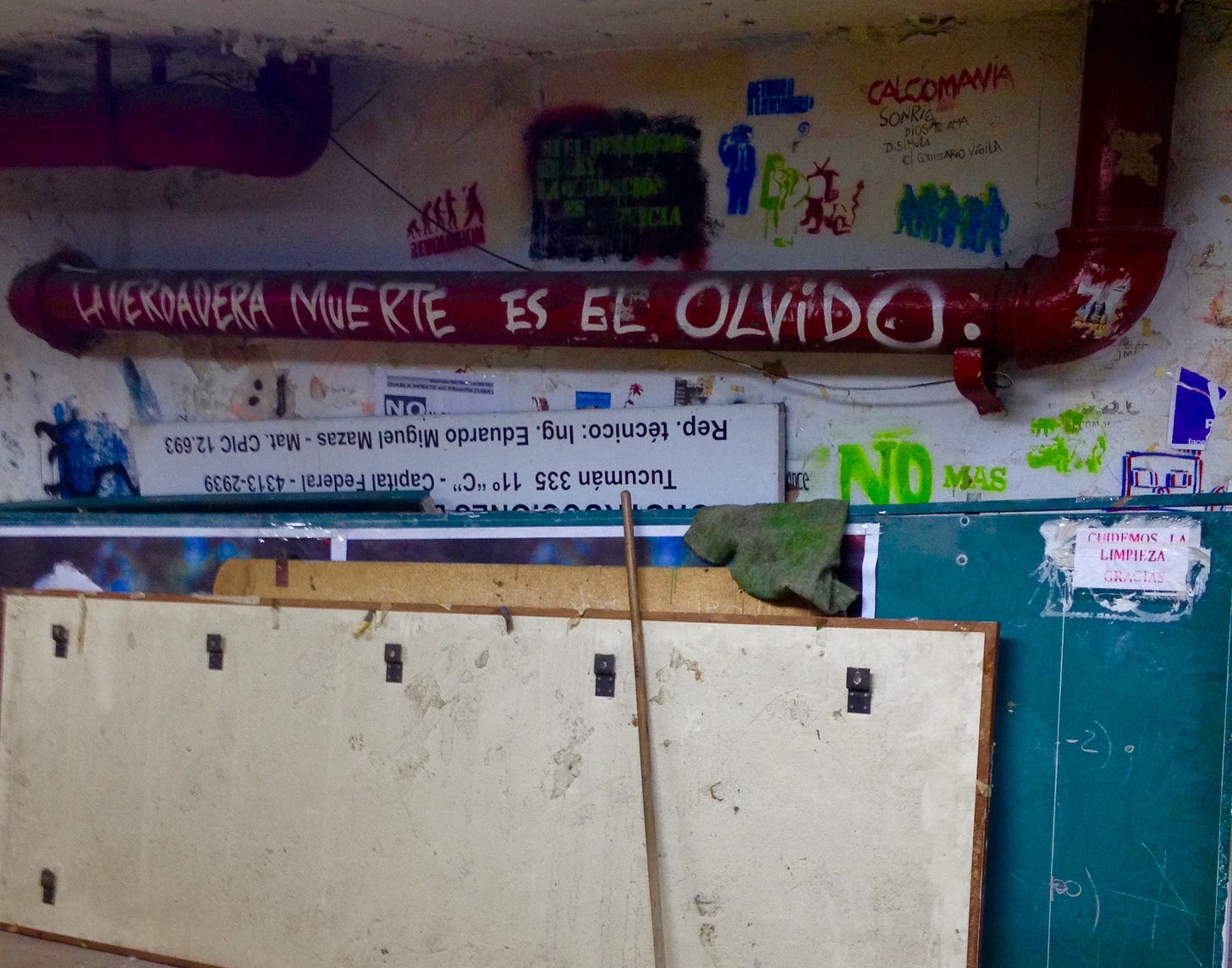

Add to this the fact that the humanities and social sciences faculties of public universities tend to be the most politicized of all faculties, and that said politicization has a strong leftist and anti-US bent, and it’s clear that we are not in Kansas—or anywhere in North America—anymore. Lectures also tend to be 6 hours long and held once a week, usually in the afternoon and evening (to accommodate students with full-time jobs) and involve reading pages upon pages of dense theory—sociological, literary, historiography—and philosophical and academic texts all in Spanish. There are also weekly or biweekly discussion sections with the equivalent of a TA where students are expected to discuss in-depth the topics covered in the lecture. Some exams are—gasp—oral, while others involve writing a 20-40 page research paper, again, entirely in Spanish. There are also many versions of the same general and introductory classes, given the cátedra system in place, meaning a class as seemingly nondescript as “political philosophy” can be taken from a Marxist, postmodern progressive, or centrist liberal perspective5, and the local students know exactly which cátedra is which. As for books? You have the fotocopiadora for that (no one cares about copyright laws). A “challenge” for “adventurous” and “daring” foreign students, indeed.

Obviously, this is all very exotic for a student coming from a picturesque American campus, with clean buildings, impeccable lawns, and spacious and well-stocked libraries. And at least in my day (a decade ago), American colleges and universities were far less politicized than they are today, so even that aspect of the Latin American public university was considered very foreign, very culturally shocking. And perhaps it still can be, as an estadounidense is an estadounidense, no matter how leftist or anti-imperialist they are. But for these progressive or leftist estadounidense exchange students, who are drawn to Latin America for the region’s history of struggle and subaltern relationship to the United States, studying at the public university, or rather, the humanities and/or social sciences faculties of the public university, is the cultural high point of their experience abroad. An experience that is truly “authentic.”

But what is authenticity, really? What makes anything, be it food, clothing, or an experience, authentic or inauthentic? This is a question that I return to time and time again, but was perhaps first sparked by my own experience and that of other North American students studying abroad in the Southern Cone. What is more “authentic” about la UBA or la Chile as compared to any other university? Are students at other universities not “true” Argentines/Chileans? Is a grungy leftism a more “authentic” and “genuine” expression of “local culture” than clean, well-kept campuses polished to an apolitical sheen?

The root of this (largely useless, I’ve since determined) quest for authenticity is a process of discovery and exploration of the “foreign.” As much as politically progressive and leftist North American students would shirk at the assertion, their view of “local culture” is essentially underpinned by this so-called “colonial gaze.” Their desire for “the authentic” is, at its core, a fetishization of the “exotic,” the “not-North American,” only instead of tango and cueca, it’s the local youth/student left activist scene. It’s a crude tactile and aesthetic campism of the senses (“anything North American is bad and imperialist and I’m against it”). Which brings me to another important point.

Most local students, even at these politicized faculties, aren’t activists (this isn’t to say they aren’t leftists or progressives; one can subscribe to a broadly leftist or progressive politics without engaging in organized activism). The community of militantes (activists) is actually quite small when compared to the total student body. Even among the activists, much of it is a “LARP” so to speak, a means through which to make friends, fall in and out of love, have fun, and maybe help some people on the way. Many student activists will enter national politics (Chile’s current president, Gabriel Boric, is a perfect example)—though they will inevitably moderate accordingly—but many more will leave activism (militancia) in their university days, looking back on it as nothing more than a fond, nostalgic memory. To paraphrase Galeano, the revolution will always be on the horizon.

And many, if not most (99% I’d say), North American students who spend a semester of a year at the local public humanities/social sciences faculty will relegate the memories of their time there to a similar place. So what’s the big deal? I don’t write any of this out of anger or resentment or a desire to police the behavior and feelings of others, but rather (self-) reflection, as I, too, was guilty of much of what I’ve discussed here. “Authenticity” is a slippery thing, something whose existence I’ve come to doubt, because what’s authentic (or feels authentic) to me may not be or feel authentic to you, but what I do know is that it’s something that cannot be bought and sold and packaged and marketed by professionals in the study abroad industry.

Unlike in Western Europe, where study abroad is generally facilitated through the EU-sponsored Erasmus+ program, study abroad in the United States is facilitated through a number of private companies and nonprofit organizations, with a lot more hand holding, guidance and overall customer service involved.

Given the worsening of the security situation in Mexico over the past decade or so, Argentina (Buenos Aires) and Chile (Santiago, Valparaíso/Viña del Mar) have become the go-to places for Spanish-language study abroad in Latin America.

That being said, it’s generally a given that state universities are more academically rigorous and well-regarded than private ones (there are some exceptions, such as Santiago de Chile’s Catholic University and Torcuato di Tella University in Buenos Aires). But for an American study abroad student, less rigorous classes—especially ones given in a second language—are often desirable and preferred.

Chilean higher education differs from that of its cross-border counterpart, not just because public universities aren’t tuition-free but because the real division isn’t between public and private but rather “traditional” and “non-traditional,” with the traditional (public and private, usually Catholic) universities considered “better” than the “non-traditional” (exclusively private) ones. This is a result of higher education reforms implemented during Pinochet’s dictatorship, which you can read more about here.

Centrist liberal is about as conservative as you’re going to get at these faculties.